Post-1948 Planning Report: 2017 Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan

This post was guided by Cities, Space, Place & Time, a graduate course at Tufts University. The goal of this assignment was to gain spatial understanding of the 2017 Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan and to understand the evolution of Open Space through time and space as it relates to the pre-1948 report on Children’s Playgrounds in Boston: An Evaluation of Space and Location.

Introduction

The 2017 Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan was prepared by Malden Open Space Steering Committee and Metropolitan Area Planning Council with the primary objective to ensure that community’s priorities regarding open space are being addressed as the City identifies new funding opportunities and seeks mitigation for impacts of new development. This paper focuses on the first important issue and critical need addressed in the Open Space Plan, developing Malden River as new open space. Additionally, this paper addresses how the City will ensure that adequate open space is provided as new development occurs in Malden. These critical needs were identified through community forums, Open Space Recreation survey, and by the Open Space and Recreation Plan Update Committee. (p. 1)1 To this end, the plan designed a seven-year action plan to address major needs including public access to the riverfront, acquisition and protection open space, environmental remediation, and land use control.

Root Causes

1. Migration

After the late 19th century rapid industrialization era, population growth in the Cities rapidly grew and providing for children’s needs became challenging. Until 1998, Malden faced a serious problem regarding space for classrooms and the City decided that the best course of action was to build new public schools on existing parks to meet their needs. (p. 17)2 However, this action was decided on the condition that new parks would be created to mitigate the loss of open space taken through construction of new classroom space. (p. 17)3

Figure 1 depicts major homes and buildings in Malden in 1795 and Figure 2 is a view of the City of Malden in 1881. The City was both an industrial center and a residential hub that included six factories that manufactured products such as rubber shoes and leather goods next to the Malden River.4

Figure 1 Malden in 1795 depicting major homes and buildings / Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library

Figure 2 Malden in 1881 with a population of 12,000 when city was both a residential suburb and an industrial center / Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Librar

2. Industrial Legacy

Because Malden used to be an industrial center with factories that were located along the banks of the Malden River, the use of the river was established for industrial purposes. (p. 13)5 The construction of the Boston and Maine Railroad sparked industrial development along the river and supported war efforts for United States.6 With increase in additional industries along the river such as chemical manufacturers, the river was dredged, contributing large volumes of waste disposal in the river.7 Without environmental regulations that prohibited pollution at this time, Malden River became a dumping ground.8 By 1920, heavy industry along the river had closed down, but the river remains contaminated because of its industrial legacy.9

Serving the Interest of Malden Residents

1. Public Access to the Riverfront

The first critical need and important issue identified in the Open Space Plan includes the development of Malden River as new open space. To this end, the open space plan identifies the continued implementation of the Malden River Greenway and new developments adjacent to the Malden River that will provide public access for pedestrians to the riverfront, pursuant to the waterways licensing program: Massachusetts General Law: Chapter 91 Public Waterfront Act. (p. 31)10 These developments include a new 75,000 SF office building and renovation of existing building and site by National Grid. (p. 31)11 Several additional commercial development opportunities will provide both public and private open space are identified on p. 31 of the Open Space Plan.12 The City also lists leveraging the Chapter 91 process to acquire easements for creation of new pathways as an action item. (p. 100)13

Chapter 91 seeks to preserve the rights of the public and guarantee the use of waterways for public purpose.14 Additional information regarding rights afforded to the public pursuant of the Chapter 91 Public Waterfront Act can be found in 2018 publication by the Conservation Law Foundation, “People’s Guide to The Public Waterfront Act.”15

2. Recreation Opportunities

One other critical issue addressed in the Open Space Plan includes enhancing recreational opportunities of the existing Northern Strand Community Trail, a 3-mile bike path between Everett & Revere. One goal in the plan is to enhance and identify new opportunities for multimodal trail network through new walking routes to the Malden River. (p. 100)16

To this end, the City has worked to towards the completion of the Northern Strand Community Trail ($1.1 M) as part of many action steps identified in the 2010 Plan, spending more than $20 million on open space and recreation projects. (p. 1)17 Additionally, the plan states a new Malden Police Station (24,000 SF) will provide an indoor community room with access to the Northern Strand Community Trail. (p. 31)18

Proposed Reforms or Policies

The Open Space Plan addresses development impacts that are regulated through state and local permitting processes including recommendations for public access to the riverfront, acquisition and protection open space, environmental remediation, and land use control.

1. Public Access to the Riverfront

The Open Space Plan emphasizes the State waterways licensing program requirement for developments to provide public access to the Malden River, an under-enforced regulation that is currently not prohibiting landowners to make decisions and therefore discouraging citizens from accessing their waterfront. (p. 54)1920 According to the action items outlined in the Open Space plan, the City aims to leverage the State’s Chapter 91 process and enhance public access to the Malden River through easements that will allow creation of new pathways. (p. 100)21

2. Acquisition and Protection of Open Space

Privately owned land is considered protected if it has a permanent deed restriction under Article 97, such as an Agriculture Preservation Restriction or a Conservation Restriction, that guarantees its open space or conservation use.22 According to the Open Space plan, the City aims to review any privately-owned land that becomes available for sale for new open space opportunities and pursue acquisition of other sites for open space and recreation development. (p. 100)23 A full list of recent growth that provides new open space can be found on page 30 of the Open Space Plan.24

Another strategy, though it doesn’t protect open space, allows for longevity of the Northern Strand Community Trail. This Northern Strand Community Trail is located in the abandoned railroad right-of-way, and though not permanently protected, is the subject of a 99-year lease between the City of Malden and state transportation authority (MBTA). (p. 66)25

3. Environmental Remediation

The Open Space Plan emphasizes that the City’s Conservation Commission of the state Wetlands Protection Act requires protection of areas in the flood plain and City Public Works ordinances require larger developments to address stormwater management and development impacts. (p. 54)26 One major environmental challenge is to adequately manage stormwater, where municipalities will be required to encourage green infrastructure practices in its permits that will allow for treatment and infiltration of stormwater before reaching the Malden River. (p. 53)27

4. Land Use Controls: Zoning

Lastly, the City of Malden has made substantial revisions to its zoning ordinance since 2010 regarding open space requirements for residential uses, including specifications that open space be pervious and visible to the public and a minimum of 50% located in yard setback areas. (p. 32)28 Additional land use controls can be found on page 32 of the Open Space Plan.

Short and Long-Term Consequences

The short-term consequences of the 7-year Action Plan identified in the Open Space Plan include ongoing efforts to review any privately-owned lands that become available for sale for open space opportunities, inventory of vacant lands that are suitable for conservation, protected open space, and/or food production, and improving/increasing the utilization of existing recreation fields. (p. 101 -106)

Through leveraging the States Chapter 91 License and through new land use control measures such as setbacks for open space, the City will expand public access to the Malden River. 105)30 Other long-term consequences of the 7-year Action Plan identified in the Open Space Plan will include an increase in recreational resources through acquisition and protection of open space with full range of access to diverse populations, an increase in public awareness and in educating the community about recreation resources, removal of barriers that prevent access for the disabled, elderly, and special needs populations, and expansion of community opportunities such as walking routes to the Malden River, gardening and urban agriculture opportunities, and improvement of the Northern Strand Community Trail. (p. 101 -106)31

The Evolution of Open Space Planning: 1948 Compared to 2017

While analyzing the 1948 plan, Childrens’ Playgrounds in Boston: An Evaluation of Space and Location, I learned policies such as sale of recreation to be used for new recreation and the ability for the City of Boston Planning Board to review and study any sale of municipally owned lands before committing to a purchase as one strategy to ensure acquisition and protection of open space. This reform standard, compared to the 2017 Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan, has continued with City of Malden aiming to review private land for new open space opportunities and pursue acquisition of other sites for open space and recreation development. Along with such reforms there are new policies that were not introduced in the 1948 plan for Children’s playgrounds in Boston, such as unprotected open spaces being subject to a lease between the City and other agencies and land use controls regarding open space requirements for all types of residential uses. Policies and reforms for protection and increase in environmental assets have continued to evolve overtime.

Demographic and Economic Context

As identified by Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Environmental Justice areas includes one or all three criteria: (p. 6)32

i. Households earn 65% or less of the statewide household median income.

ii. 25% or more of the residents are minority.

iii. 25% or more of the residents are lacking English language proficiency.

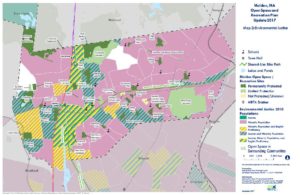

Figure 3 Environmental Justice Areas in Malden. The entire City of Malden with the exception for two census block groups include Environmental Justice populations / Malden Open Space Steering Committee and Metropolitan Area Planning Council

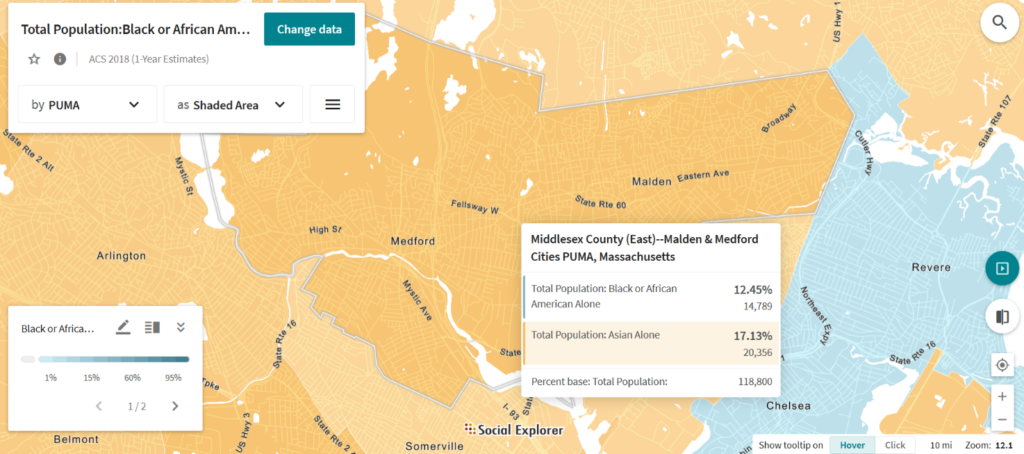

The entire City of Malden with the exception for two census block groups include Environmental Justice populations (see Figure 3 for reference). (p. 26)33 According to Social Explorer, a mapping site that provides access to demographic information, Malden has seen a huge increase in percentage of African American and Asian population from 1950-2018 (see Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4 Showing Demographic Change in African American Population from 1950-2018 / Aqsa Butt, Social Explorer

Figure 5 Showing Demographic Change in African American Population from 1950-2018 / Aqsa Butt, Social Explorer

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s (MBTA) Orange Line stations in Oak Grove and Malden Center encouraged the redevelopment of the City’s downtown after the Great Depression slowed down Malden’s growth and progress. (p. 14)34 Since the 1990’s, the City has undertaken several revitalization projects that have helped bring additional business activity. (p. 14)35 The Open Space Plan does an excellent job at addressing the current demographic of Malden. Its seven-year action plan states that any agreement for use of city-owned open or recreational assets will ensure that environmental justice communities be equitably treated and that critical needs identified through this plan correlate with the City’s environmental equity efforts, including the effort to develop the Malden River as open space. (p. 54)36 However, the plan fails to address anti-displacement policies, reforms, and other strategies that will mitigate the impacts of revitalization for low-income populations.

Environmental and Spatial Context

Open space statistics in Malden show that there are approximately 120 people per acre of existing open space or approximately 8.2 acres of open space per 1,000 people, which is slightly higher than the city-wide average for Boston (7.59 acres) (p. 23)37 38 However, it is important to note from the pre-1945 report of, Childrens’ Playgrounds in Boston: An Evaluation of Space and Location, that though total area of open space in overall Malden could theoretically provide the standard of minimum space per person, if does not mean that the size and distribution of these spaces was strategically planned and accounts for factors such as population density. (p. 7 and p. 29)39 These spaces can be either not large enough or inaccessible if they are surrounded by non-residential uses. (p. 7 and p. 29)40 Further analysis such as the one observed in the pre-1945 plan could have determined the sufficiency of open space through factors such as size and location of each open space, addressing maximum allowable walking distance (between ¼ mile to ½ mile radius), with consideration of barriers such as traffic and topography.(p.15)41

The Long-Term Consequences of Actions

The long-term consequences of not spatially analyzing open space are obvious. Location of open space should be based on several factors that above environmental conditions address factors such as accessibility and size. This will determine utilization of open spaces for future generations to come. Lastly, the clean up efforts addressed in the plan are highly important as access to open space near Malden will only serve the needs of residents if the water quality is addressed through stormwater strategies and volunteer cleanups.

Decisions, Governance, and Participation

In order to provide better service to the public, all open spaces should maximize equity in addition to access. The community participatory process in this Open Space Plan is highly beneficial for communities of color and lower income population. A community voice is needed to contest for change, which is clearly addressed in this Open Space Plan.

When it comes to the protection of open space, no local land trust was appointed or addressed in the Open Space Plan. A local land trust in Malden could be highly beneficial as a partner as it will provide protection of open spaces that remain vulnerable to future development. A partnership between the municipal government and non-profit could provide a power dynamic that further mobilizes efforts of safety and accessibility. Plan making today, has shifted in terms of having more than just one actor (the City) and should include more partnerships that collectively bring change to communities.

1“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan,” accessed November 5, 2019, https://www.cityofmalden.org/DocumentCenter/View/861/Malden-Open-Space-and-Recreation-Plan—Final-PDF.

2“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

3“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

4“City of Malden – Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center,” accessed December 7, 2019, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:x633fc80h.

5“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

6“Experiencing the Legacy of a Proud Industrial Past…,” Friends of the Malden River (blog), April 19, 2013, https://maldenriver.wordpress.com/history/.

7“Experiencing the Legacy of a Proud Industrial Past….”

8“Experiencing the Legacy of a Proud Industrial Past….”

9“Experiencing the Legacy of a Proud Industrial Past….”

10“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

11“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

12“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

13“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

14“Chapter 91, The Massachusetts Public Waterfront Act,” Mass.gov, accessed December 7, 2019, https://www.mass.gov/guides/chapter-91-the-massachusetts-public-waterfront-act.

15“CLF Peoples Guide Public Waterfront Act,” accessed December 7, 2019, https://www.clf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/CLF-Peoples-Guide-Public-Waterfront-Act-Dec28.pdf.

16“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

17“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

18“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

19“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

20“Experiencing the Legacy of a Proud Industrial Past….”

21“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

22“Massachusetts Document Repository,” accessed December 4, 2019, https://docs.digital.mass.gov/dataset/massgis-data-protected-and-recreational-openspace.

23“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

24“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

25“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

26“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

27“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

28“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

29“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

30“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

31“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

32“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

33“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

34“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

35“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

36“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

37“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan.”

38Cook et al., “Open Space & Recreation Plan 2015 –2021.”

39Boston (Mass.). City Planning Board, Childrens’ Playgrounds in Boston: An Evaluation of Space and Location, 1948, http://archive.org/details/childrensplaygro00bost.

40Boston (Mass.). City Planning Board, Childrens’ Playgrounds in Boston: An Evaluation of Space and Location, 1948, http://archive.org/details/childrensplaygro00bost.

41Boston (Mass.). City Planning Board.

References:

Boston (Mass.). City Planning Board, Childrens’ Playgrounds in Boston: An Evaluation of Space and Location, 1948, http://archive.org/details/childrensplaygro00bost.

“Chapter 91, The Massachusetts Public Waterfront Act,” Mass.gov, accessed December 7, 2019, https://www.mass.gov/guides/chapter-91-the-massachusetts-public-waterfront-act.

Christopher Cook et al., “Open Space & Recreation Plan 2015 –2021” (Boston Parks and Recreation, January 2015), https://documents.boston.gov/parks/pdfs/OSRP_2015-2021.pdf.

“City of Malden – Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center,” accessed December 7, 2019, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:x633fc80h.

“CLF Peoples Guide Public Waterfront Act,” accessed December 7, 2019, https://www.clf.org/wp- content/uploads/2018/12/CLF-Peoples-Guide-Public-Waterfront-Act-Dec28.pdf.

“Experiencing the Legacy of a Proud Industrial Past…,” Friends of the Malden River (blog), April 19, 2013, https://maldenriver.wordpress.com/history/.

“Malden Open Space and Recreation Plan,” accessed November 5, 2019, https://www.cityofmalden.org/DocumentCenter/View/861/Malden-Open-Space-and- Recreation-Plan—Final-PDF.

“Massachusetts Document Repository,” accessed December 4, 2019, https://docs.digital.mass.gov/dataset/massgis-data-protected-and-recreational-openspace.

“Social Explorer,” accessed December 6th, 2019, https://www.socialexplorer.com/.

Sources of Graphics:

Figure 1: Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library (https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:pv63g500w.)

Figure 2:

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library (https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:x633fc80h.)

Figure 3: Malden Open Space Steering Committee and Metropolitan Area Planning Council

(http://www.mapc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/8.29-FINAL_Malden_OSRP.pdf)

Figure 4: Aqsa Butt, Social Explorer

Figure 4: Aqsa Butt, Social Explorer

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post